A (little) history of the voluntary carbon market

Updated in August 2025

The voluntary carbon market (VCM) is getting a lot of new attention recently and for those to which the topic is new, might get an impression that it’s a brand new market. While it is young compared to centuries-old markets like the stock market, calling it ‘brand new’ would be unfair. In reality, the origins of this market can be traced back all the way to 1990s.

So what’s the history of this market? Where did it come from and why is it getting so much attention in the recent years?

What is the voluntary carbon market?

It’s important to note that there are two types of carbon markets: compliance and voluntary carbon markets. Even though both markets trade in emissions, these take different forms and have different market participants:

- Compliance markets are regulatory, closed systems where participants are determined by the government and the participants trade in allowances or permits, which allow them to emit greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions

- The voluntary carbon market trades credits (often referred to as offsets) between project developers and companies voluntarily purchasing credits to offset their environmental harm

What’s the relationship between voluntary and compliance markets?

While the focus of this article is on the history of the voluntary carbon market, it doesn’t exist in a vacuum and wouldn’t exist without the influence of regulations and compliance markets. It can be argued that the voluntary carbon market came to fill the gap left by the limited reach of the compliance markets. This means the history of voluntary market is influenced by the regulatory frameworks and changes to compliance markets, whether that is Kyoto Protocol in the early 2000s or the Article 6 happening as part of COP negotiations now (more on both below).

When did the voluntary carbon market begin?

The origins of private companies investing in carbon projects in order to offset their emissions goes all the way back to the 80s. In fact, the first land-based carbon project was initiated in 1988, when the World Resource Institute (WRI) advised the energy firm Applied Energy Services to plant trees and slow deforestation in Guatemala to offset the emissions of their coal plant in the US.

The idea behind it was simple. One tonne of emissions into the atmosphere has the same effect on climate, regardless of where it came from. So by the same logic, reducing a tonne of carbon emissions released to the atmosphere has the same benefit wherever it happens.

So offsetting by private companies is over 30 years old! And since then, the market has developed and more and more corporates have begun investing in projects.

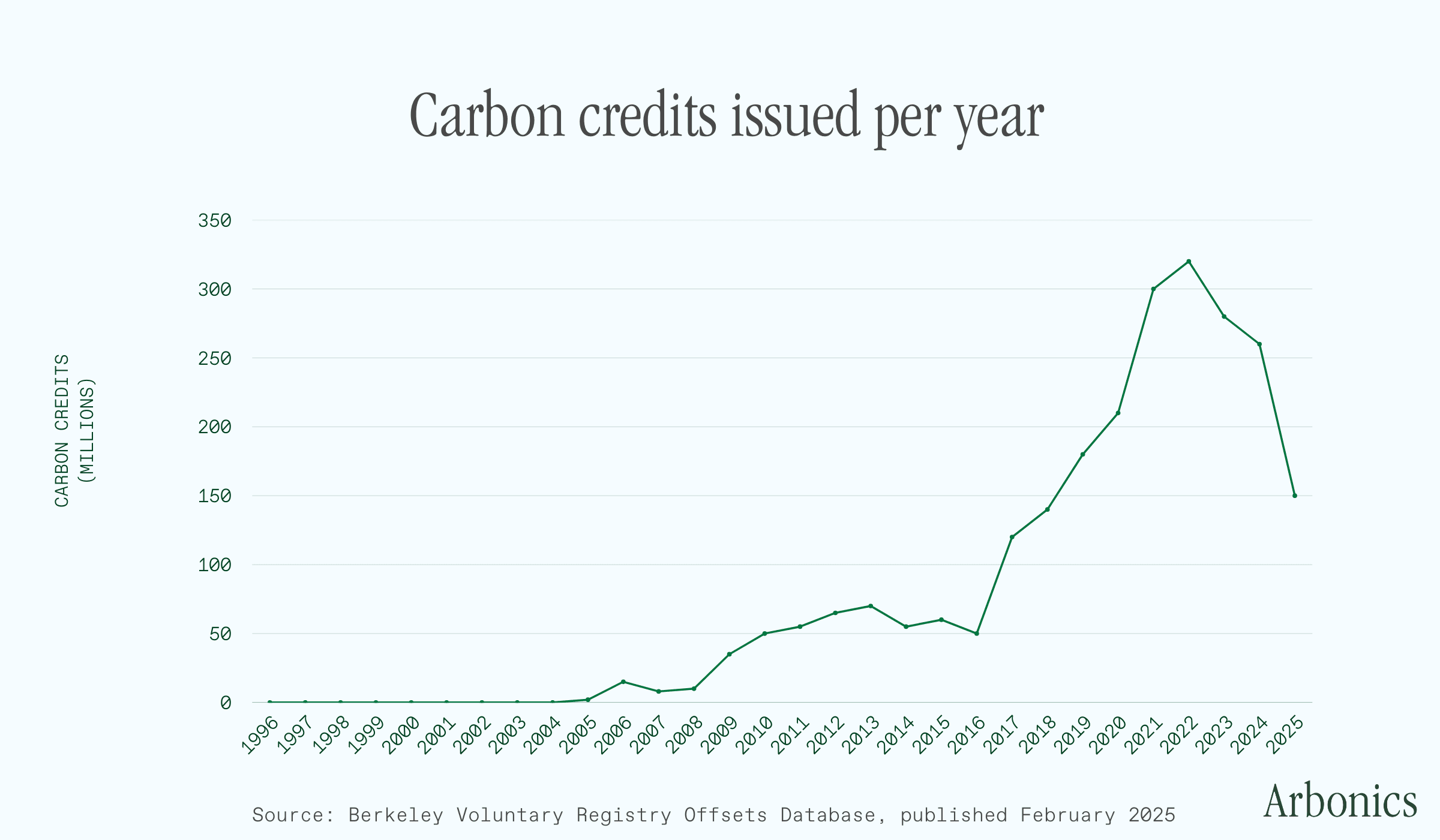

Data from the from the Berkeley Voluntary Registry Offsets Database v7. Phases from the Verra and ICROA infographic.

From 1990 to 2007: early market formation and innovation

The first US project revealed corporate interest in addressing its environmental impact. Around the same time, the international community became increasingly aware of the threats to the climate and our environment, which led to the first agreement to limit and reduce the greenhouse gases in the atmosphere under the Kyoto Protocol.

This international treaty was introduced in 1997, ratified in 2005, and was the first of its kind aimed at addressing climate change. It introduced compliance mechanisms such as the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) and Joint Implementation (JI), which allowed developed countries to invest in emissions reduction projects in developing nations to offset their own emissions. The idea of offsetting had made it to country-level.

The CDM was developed to help nations meet Kyoto targets, but it also served to shift a lot of capital from the developed world to the developing world. During the mid 90s, climate policy was focused on contraction and convergence. That is, the developed world aimed to contract emissions intensity, while allowing the developing world to converge towards middle income emissions intensities.

The CDM was designed to assist this process but projects weren’t particularly efficient (from a carbon offsetting perspective). For various reasons, which we are not going into here, there was also a decline in the compliance demand, so the CDM had leftover supply, which began serving the voluntary demand.

While imperfect, CDM projects laid the groundwork for the modern Voluntary Carbon Market (VCM). They pioneered international carbon trading and spurred the creation of carbon projects in the developing countries. Beyond regulatory frameworks, non-governmental organisations and environmentally-conscious businesses seized the opportunity to support positive environmental initiatives voluntarily. The concept of carbon neutrality gained prominence, with individuals, companies as well as events such as the 2002 Winter Olympic Games in Salt Lake City were measuring their footprint and compensating it by investing in carbon projects.

This voluntary action highlighted the need for verification, leading to the establishment of key credit standards and registry bodies that are still active today, such as the Gold Standard (2003), American Carbon Registry (2007), and Verra (2007). You can learn more about their role here.

From 2007 to 2016: consolidation and strengthening

The demand for carbon offsets grew, partly due to high-profile commitments by major corporations to achieve carbon neutrality such as Microsoft and the Walt Disney Company amongst many.

This period saw establishment of more best practises and increased engagement from the private sector. There was also an expansion in the type of projects and geographies. For example, the first REDD+ credits, which stands for “reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation in developing countries” were issued in 2011.

As sustainability and environmental, social, and governance (ESG) reporting gained importance, the voluntary carbon market became intertwined with broader sustainability strategies. And there was also an increased focus on linking these projects to the Sustainable Development Goals, which were adopted by the United Nations in 2015.

This period saw another big milestone for climate. At COP21, 196 countries signed the Paris Agreement. This replaced the Kyoto Protocol with new emission reduction targets for countries and the countries agreed a goal of limiting the global temperature increase to 1.5C. The agreement also included an Article 6 which is the section of the agreement that aims to increase climate ambition by allowing countries to voluntarily cooperate with each other to achieve their emission reduction targets. This means that, under Article 6, a country (or countries) will be able to transfer carbon credits earned from the reduction of GHG emissions to help one or more countries meet climate targets.

The devil is in the details when it comes to the implications of Article 6. Discussions and negotiations are ongoing since 2015, specifically regarding Article 6.4, which recognises the ability for companies or individuals to engage in mitigations of greenhouse gas emissions and how this is be reconciled with each country’s targets (known as nationally determined contributions or NDCs).

From 2017 until now: mainstreaming

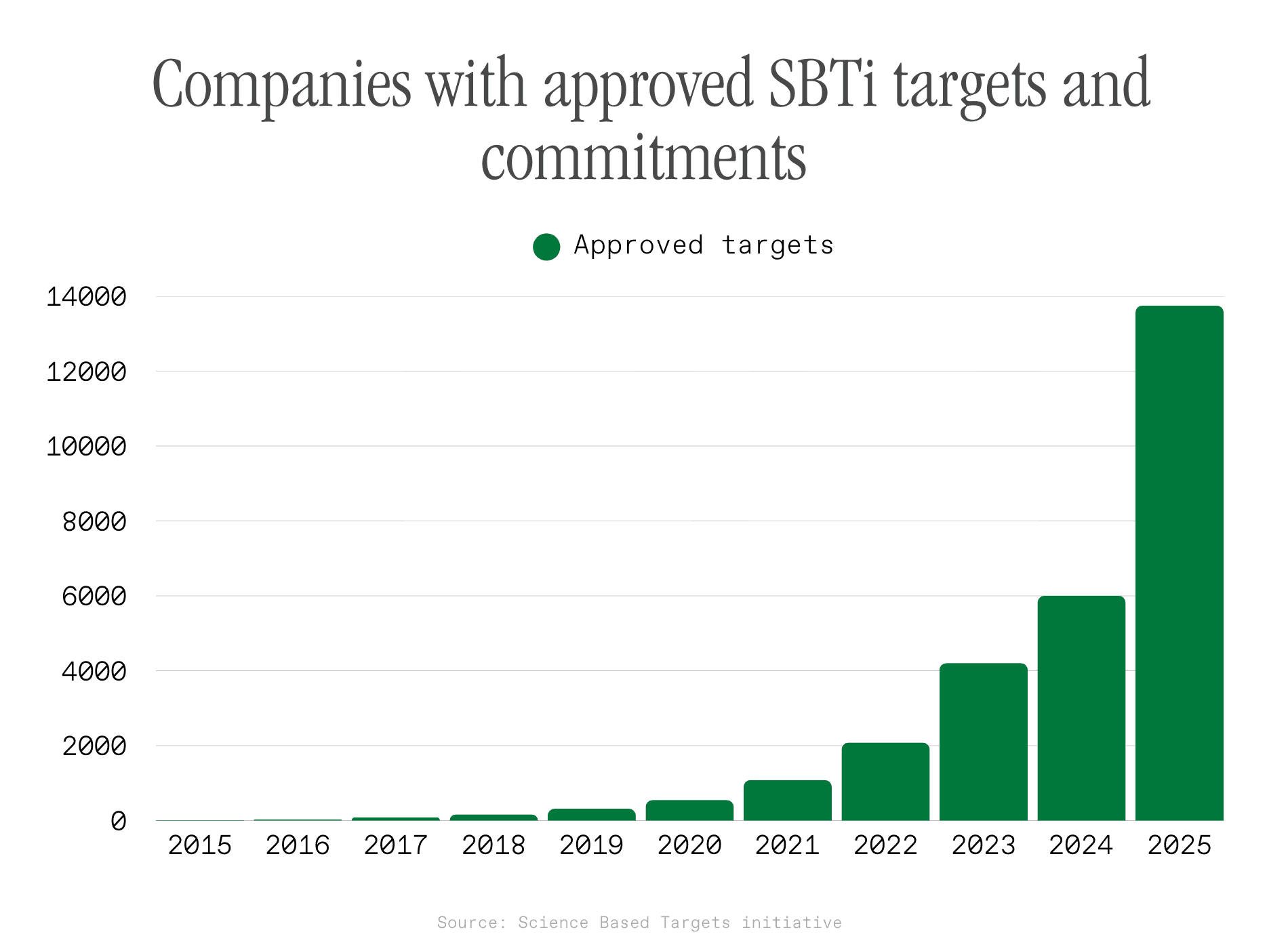

Since the late 2010s, the voluntary carbon market continued to mature, with a greater emphasis on project quality, impact measurement, and transparency. If after the Kyoto protocol the buzzword was carbon neutrality, then after Paris Agreement, the word became net zero. And since then, we’ve seen more and more companies making net zero commitments.

By 2024 over 6000 companies had Science Based Targets initiative's (SBTi) approved emission reduction targets.

Source: Science Based Targets initiative

This period of accelerating growth has not only driven up demand for carbon credits, but has also put pressure on the quality of projects. As urgency increases, various initiatives pop up to build best practises in the market, such Taskforce for Scaling Voluntary Carbon Markets, Integrity Council for the Voluntary Carbon Market (ICVCM), Voluntary Carbon Markets Integrity Initiative (VCMI) and many more. To help buyers identify high-quality projects, rating agencies like BeZero and Sylvera emerge as well.

This is the point at which the market got more attention, not just from industry participants and policy makers, but also the general public. Increased media coverage and investigations into historical projects expose many shortcomings (especially around additionality) that made many market participates level-up the quality of their projects. In addition, large corporate investors began to look deeper:

- How are the credits generated?

- What evidence supports the project's claims?

- What social and ecological impacts does it deliver beyond carbon removal?

This shift began to shift both demand and supply. The voluntary carbon market continues to adapt to these changing expectations and demands, integrating technological advancements and exploring innovative mechanisms to enhance credibility.

Looking to the future

Given the amount of investment and new players emerging in the space, the market is evolving rapidly. Where exactly will it go? This is hard to predict, but here are a few themes that are starting to emerge.

Flight to quality with new standards and improved methodologies

Increasing criticism of avoidance-type credits is likely to decrease their popularity with potential buyers even more, who fear facing accusations of greenwashing. This is likely to reduce the issuance and retirement of these credits, while putting more pressure on the supply of removal-type credits.

Alongside the established verifiers such as Verra and Gold Standard, new standards emerge to tackle quality concerns. One such example is Isometric. These new standards will bring constantly improved methodologies, which will help to support this flight to high-quality credits.

Emphasis on transparency

The core issue of transparency and traceability in the voluntary carbon market persists. We expect new strides in MRV and industry standards to make project information more broadly available. Satellite imagery and remote sensing are already making it possible to track forest cover, biomass growth, and land-use change with far greater accuracy than before. AI and machine learning are helping to process these large data streams, spotting anomalies and validating results at scale. Together, these tools can reduce information gaps and make project data far more transparent and accessible.

We recently explored these themes in more depth during a webinar with Cecil Earth, looking at what’s next for forest monitoring and how technology is reshaping the field. Watch the webinar here.

Price polarisation

As quality becomes more a keyword, we can expect impacts on price. In particular, we would expect to see a polarised distribution: credits perceived as low quality are expected to converge below $10/tonne, while higher-quality credits are more likely to appreciate significantly - with EY’s Net Zero Centre predicting prices of $80–150 per tCO₂e by 2035.