5 mistakes to avoid when afforesting

When talking about afforestation (planting new forests), often among the first questions people ask me is: “How do you make sure you’re not doing more harm than good?”

This is a very valid question. So let’s tackle this directly - let’s cover the 5 biggest things that afforestation projects could do wrong, and how we can avoid them.

1. Planting non-native trees

The first and possibly most wide-spread issue with large planting projects is planting trees that are not native to the environment where the project takes place.

Non-native trees can disrupt the balance of the local ecosystem and lead to unintended consequences, such as decreased biodiversity and reduced soil quality.

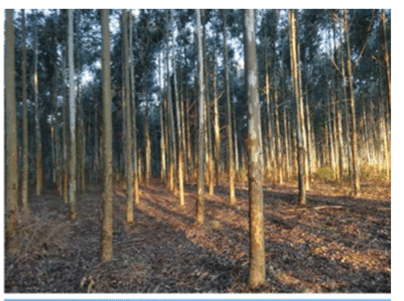

For example, in some parts of the world, eucalyptus trees have been planted for their fast growth and potential for timber production. However, eucalyptus trees are not native to many of these regions, and their introduction has led to the displacement of native species and the depletion of local water resources. For example, a study of eucalyptus plantations in Argentina by (Phifer et al, 2016) showed that these had far fewer bird species and understory plants compared to native forests and even less than other intensely managed lands, such as blueberry and citrus farms.

Large-scale mature eucalyptus plantation. Photo courtesy of Phifer et al 2016.

What to do instead

Simple - plant native trees! In much of Europe, this is also regulated by law, with forestry law often limiting the types of trees that can and cannot be planted. But regardless, planting native trees helps make the resulting forest as attractive as possible for a variety of other species, increasing the biodiversity of your forest.

2. Planting without a maintenance and survival plan for saplings

Another major issue that afforestation projects can face is the lack of a maintenance and survival plan for saplings. Without a proper plan in place, newly planted trees may not receive the care and attention they need to thrive, leading to high mortality rates and the potential failure of the newly planted forest.

For example, in some projects, saplings are planted without proper soil preparation or irrigation, leading to their death due to lack of water or nutrients. In other cases, the trees may be planted too close together, leading to overcrowding and competition for resources. Or, as has happened in some “plant a tree” style projects, the saplings are simply abandoned after planting, leading to large losses due to the young trees losing the battle to weeds and grass, or simply being eaten by moose.

A sapling protected with Cervacol, a popular moose repellent. Photo courtesy of LVM.lv

What to do instead

Make sure to take care of the saplings, especially during the first 3 years post-planting. This includes weed control and protection from moose and other herbivores with a taste for young trees.

3. Maintaining the forest as a monoculture

We’ve all heard this: planting monocultures is bad. This makes a great deal of sense: a forest consisting of a single species is not biologically diverse, and it’s more vulnerable to pests and fire.

This is all true. But there's an important distinction to be made here between planting as a monoculture and maintaining the forest as a monoculture. For example, we might choose to plant spruce saplings, knowing that surrounding birch trees will seed and naturally regenerate small birches between the spruces a few years later. In such a case, while we're primarily planting a single species, we are nonetheless creating a mixed forest by encouraging other species.

Furthermore, some forests (such as pine) naturally tend to be single-species when it comes to trees - but make up for it by having an abundance of understory species such as blueberries.

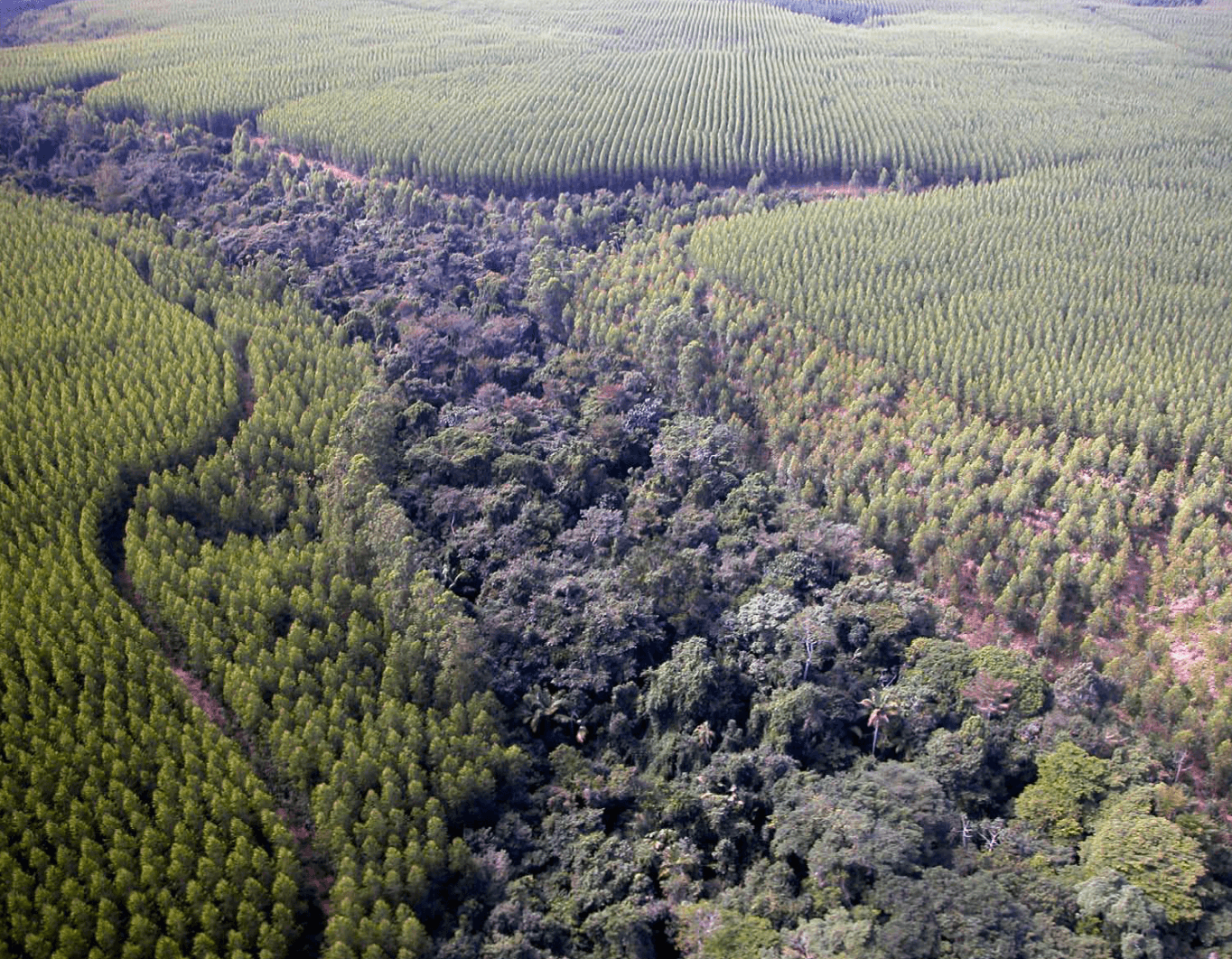

Monoculture plantations on either side of a native forest. Photo courtesy of Waring/Gonzalez-Benecke for OSU.

What to do instead

Encourage diversity of species - both through planting (if practical) and ongoing management practices. This might mean planting at a lower density to encourage natural “infill”, and avoiding clearing out other species during maintenance harvests.

4. Planting on land that has unique habitats or high biodiversity value

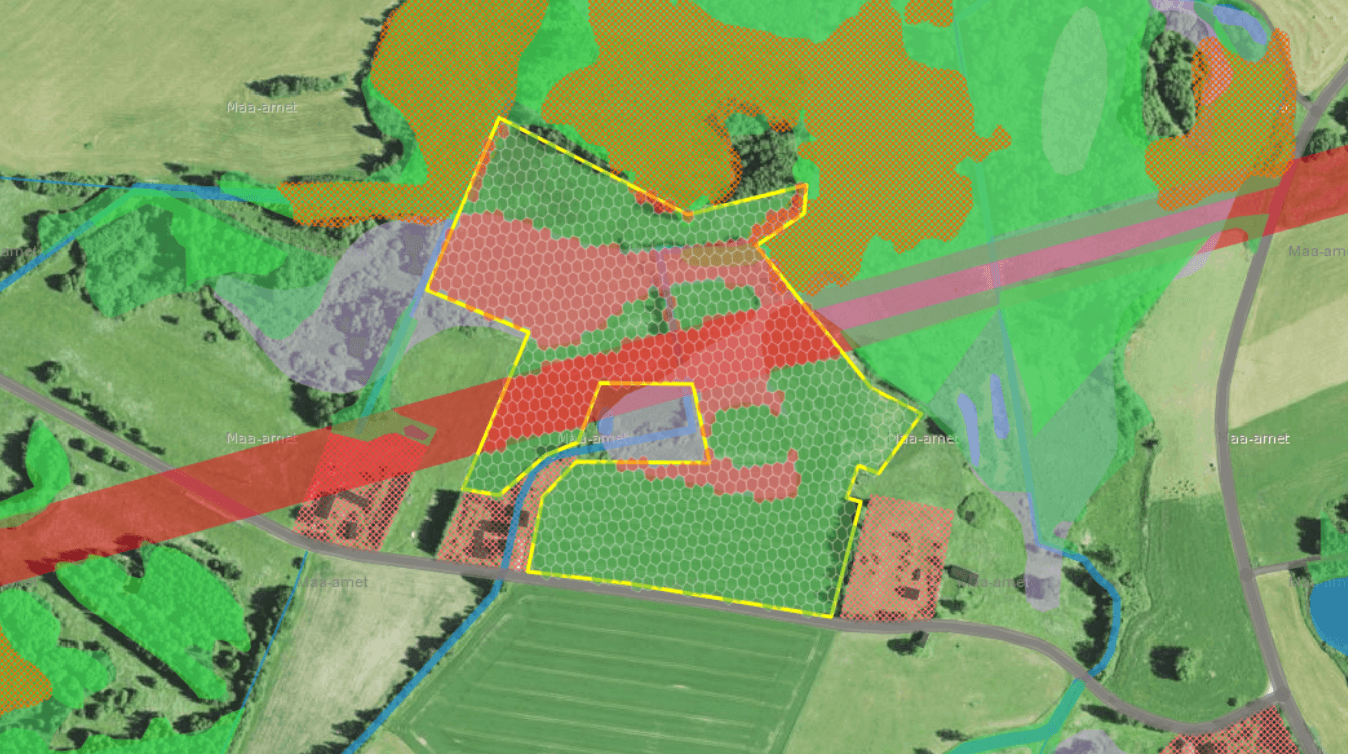

Not all land can or should be forestland. There are a range of unique biomes - such as alvars, highly diverse semi-natural grasslands etc - which are valuable in themselves. Converting these to forestland could actually decrease biodiversity. This is why it's important to carefully assess land prior to afforestation and make sure we're only planting on land that could benefit from being converted to forests. The best way to do this is through a rigorous, data-based approach - at Arbonics, we've developed our own in-house platform which highlights specific high-value areas as unsuitable for afforestation. As we continue to build out the solution, we are constantly adding more detail about land to make these decisions even more rigorous and data-led.

Example of data-based land analysis on the Arbonics platform.

What to do instead

Make sure to assess any land that is planned for afforestation - check that it's not listed as a high-value habitat. Avoid planting in ways that might destroy existing biodiversity.

5. Planting on land that is essential for food production for the local community

It might be tempting to use the most productive farmland available for afforestation - because that means faster tree growth and therefore more CO2 sequestered, right? However, we can't ignore that land has various roles, and growing food for our communities is a key one. If we turn all farmland to forest, we may cause food insecurity and shortages. This is obviously not a good outcome. In order to avoid these negative externalities, we need to use only land that is suitable for afforestation, and also do a risk assessment to make sure we're not harming food production.

What to do instead

Focus afforestation plans on land that is not currently used to its highest potential. The best land for afforestation is low-quality or abandoned farmland and pastureland - by keeping tree planting to these plots, we can avoid any potential conflict with food production.

As a bonus consideration, do not plant on land that has other historical or cultural value - for example, Stonehenge is not a great candidate for afforestation, so we should not be planting there.

- 1. Planting non-native trees

- What to do instead

- 2. Planting without a maintenance and survival plan for saplings

- What to do instead

- 3. Maintaining the forest as a monoculture

- What to do instead

- 4. Planting on land that has unique habitats or high biodiversity value

- What to do instead

- 5. Planting on land that is essential for food production for the local community

- What to do instead